The Three-Age System: A Framework for Prehistoric Chronology

To understand the history of bihar, let the Three-Age System is a methodological concept used in archaeology, history, and anthropology to classify prehistoric periods based on technological advancements in material use. It was developed by C. J. Thomsen between 1816 and 1825, categorizing human history into the Stone Age, Metal Ages. This system was later refined, including the introduction of subcategories within the Stone Age.

The study of prehistory categorizes human development into three distinct ages:

The Stone Age and Its Subdivisions

The Stone Age is the earliest and longest phase of human prehistory, defined by the use of stone tools. British researcher John Lubbock, in 1865, divided it into the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) and Neolithic (New Stone Age) periods. The Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) was later introduced by Hodder Westropp in 1866 as an intermediate phase.

- Paleolithic Period (Old Stone Age) – Early human tools and hunting practices.

- The earliest phase of the Stone Age, characterized by hunter-gatherer societies.

- People used heavy-chipped stone tools and relied on group hunting of large animals.

- Mesolithic Period (Middle Stone Age) (c. 12,000 – 8,000 BP) – Shift from hunting to early agriculture.

- Transitional period between the Upper Paleolithic and Neolithic.

- In the archaeology of India, the Mesolithic, dated roughly between 12,000 and 8,000 Before the Present Period (BP), remains a concept in use.

- Marked by declining large-animal hunting and a shift to broad-spectrum foraging.

- Development of smaller, more sophisticated lithic tools (microliths).

- Some early evidence of pottery and textiles, though agriculture was not yet widespread.

- Permanent settlements began to appear, usually near water sources.

- Neolithic Period (New Stone Age) (c. 10,000 – 2,000 BC) – Transition to settled life, farming, and animal domestication.

- A significant transformation with the Neolithic Revolution (the introduction of farming).

- Shift from hunting and gathering to settled agricultural societies.

- Domestication of plants and animals (wheat, barley, sheep, cattle, and goats).

- Earliest evidence of dental surgery (bow drills for tooth drilling found at Mehrgarh, Pakistan).

- The Neolithic lasted until the emergence of metallurgy and urbanization in different regions:

- Near East and Mesopotamia: Transitioned to the Chalcolithic (Copper Age) around 4500 BC.

- Ancient Egypt: Lasted until the Protodynastic period (c. 3150 BC).

- China: Lasted until 2000 BC, with the rise of the pre-Shang Erlitou culture.

- South India: Extended until 1400 BC, marked by the transition to the Megalithic period.

In South Asia, the Neolithic began around 7000 BC at Mehrgarh (Balochistan, Pakistan), where early farming and animal domestication were documented. The South Indian Neolithic (6500–1400 BC) was characterized by ash mounds and the emergence of megalithic culture.

The Metal Ages: Copper, Bronze, and Iron

Following the Neolithic period, metallurgy emerged, leading to the Copper Age (Transition from stone tools to metalwork), Bronze Age (Widespread use of bronze tools and early civilizations), and Iron Age (Development of iron tools and advanced societies), collectively known as the Metal Ages. The Copper Age was sometimes considered a transition between the Stone Age and Bronze Age, but in many periodizations, the Three-Age System remains in use to describe prehistoric chronology in Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Near East. However, this classification has limited applicability in sub-Saharan Africa, much of Asia, and the Americas, where different cultural developments occurred.

The Three-Age System provided an early framework for classifying prehistoric human development based on material culture. Over time, subdivisions such as the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic refined our understanding of technological and social progress. While this system remains relevant in certain regions, alternative models are used in areas where cultural evolution followed a different trajectory.

Timeline of Bihar: A Historical Overview

| Period | Era/Phase | Year/Date | Event/Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prehistoric Era | 1. Neolithic Age (New Stone Age) | 10800–3300 BC | Transition to settled life, farming, and animal domestication. Early settlements in Bihar |

| Ancient Period | 2. Bronze Age | 3300–1500 BC | Widespread use of bronze tools and early civilizations. Development of metallurgy and agriculture |

| 3. Iron Age | 1500–200 BC | Development of iron tools and advanced societies. | |

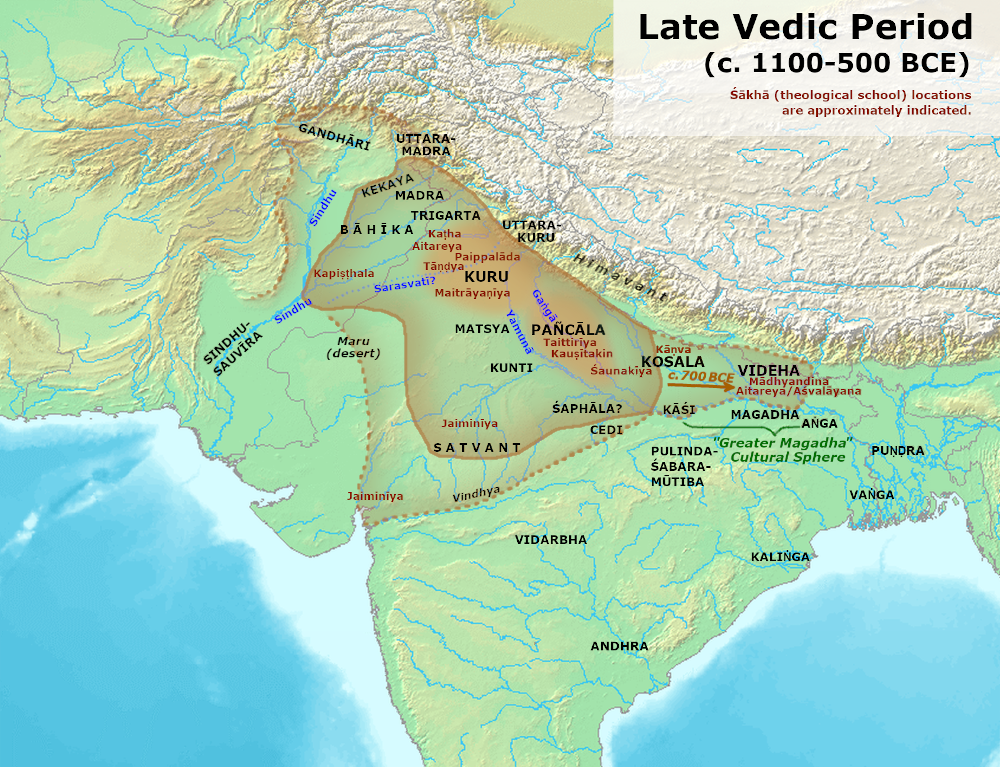

| [3.1] Late Vedic Period | |||

| 1700 BCE | King Brihadratha establishes the first ruling dynasty of Magadha | ||

| 1100-600 BCE | Republics of Videha, Magadha, and Anga rule modern-day Bihar | ||

| 8th century BCE | Sita, daughter of King Janak of Mithila, is mentioned in the Hindu epic Ramayana | ||

| 6th century BCE | Vajji Confederation established in Mithila (Vaishali as the capital) | ||

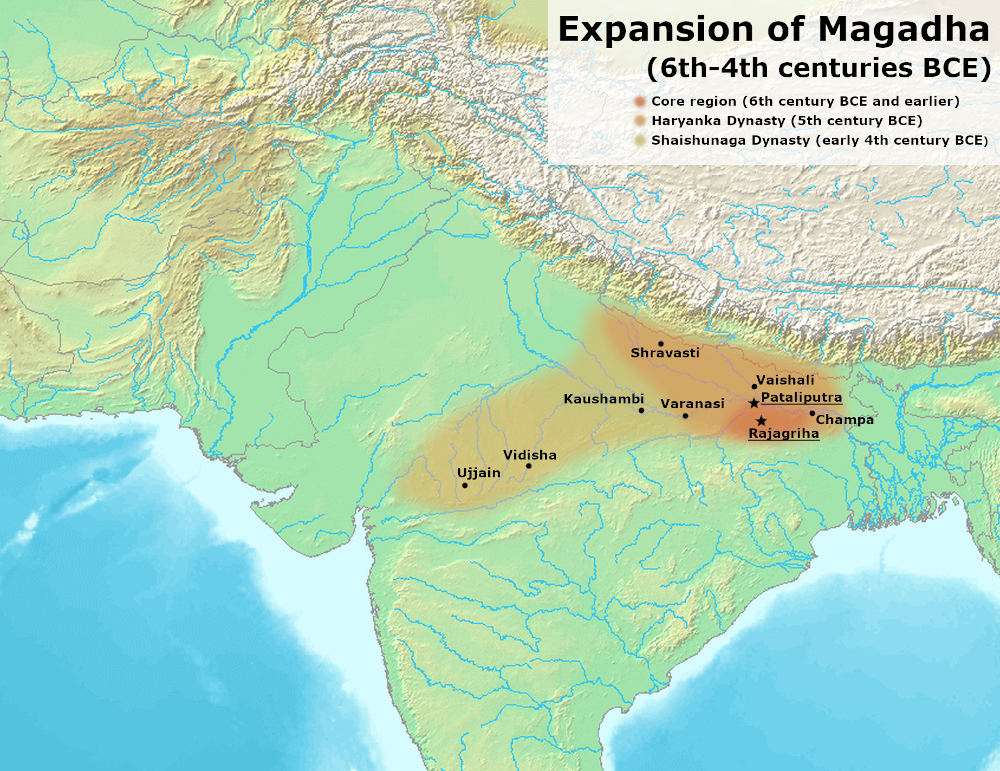

| [3.2] Rise of Magadha | |||

| 540 BCE | Magadha (Haryanka dynasty) annexes Anga | ||

| 537 BCE | Gautama Buddha attains enlightenment in Bodh Gaya; Mahavira born in Kundalpur | ||

| 492 BCE | Ajatashatru executes his father Bimbisara and takes the throne | ||

| 490 BCE | Pataliputra is established | ||

| 484-468 BCE | Magadha defeats Vajji in war and unifies Bihar | ||

| Around 460 BCE | Magadha annexes Kosala, becoming a major North Indian power | ||

| 413 BCE | Shishunaga overthrows Nagadashaka, ending the Haryanka dynasty | ||

| 400 BCE | Shishunaga defeats Pradyota dynasty, expanding Magadha’s influence | ||

| 345 BCE | Mahapadma Nanda establishes the Nanda dynasty | ||

| 345-322 BCE | Nandas introduce administrative reforms, new currency, and a massive army | ||

| [3.3] Mauryan Empire | |||

| 322-297 BCE | Chandragupta Maurya overthrows Nandas, expands Magadha into a pan-Indian empire | ||

| 304 BCE | Ashoka is born in Pataliputra | ||

| 273 BCE | Ashoka crowned Emperor | ||

| 261 BCE | Ashoka defeats Kalinga, converts to Buddhism | ||

| 232 BCE | Death of Ashoka, beginning of Mauryan decline | ||

| 4. Middle Kingdoms | 200 BC – 1200 AD | ||

| 185 BCE – 80 BCE | Shunga dynasty established by Magadh general Pushyamitra Shunga | ||

| 75 BCE – 26 BCE | Kanva Dynasties | ||

| Around 6th century-11th century | The rule of Pala and Sena dynasties in Mithila region | ||

| 600 – 650 AD | Harsha Vardhana expands into Magadha | ||

| 750 – 1200 AD | Pala dynasty expand into Magadha | ||

| 11th century- Around 1325 | Karnat dynasty rules Mithila | ||

| 5. Medieval Period | 1200 – 1750 | ||

| 1200 | Bakhtiyar Khilji destroys Nalanda and Vikramshila Universities (Start of Afghan-Muslim rule in the Magadh region) | ||

| 1200 – 1400 | Sharp decline of Buddhism in Bihar and northern India | ||

| 1250-1526 | Magadh and Mithila under Delhi Sultanate | ||

| 1526-1540 | Babur defeats Delhi Sultanate; Mughal Empire begins | ||

| 1540-1555 | Sher Shah Suri defeats Mughals, builds Grand Trunk Road, introduces rupee | ||

| 1556 – 1764 | Bihar becomes a province of the Mughal Empire | ||

| 1666 | Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth and last Sikh Guru, is born in modern-day Patna. | ||

| 6. Colonial Period | 1750 – 1947 | ||

| [6.1] British East India Company | |||

| 1757-1857 | British East India Company expands into Bihar | ||

| 1764 | Battle of Buxar: British gain tax collection rights | ||

| 1764 – 1920 | Migration of Bihari & United Provinces workers across the British world by the Company and later British government | ||

| 1857 | Indian Rebellion of 1857: Bihar becomes a key resistance center | ||

| [6.2] The British Raj | |||

| 1858 | Mughal Sultanate-e-Hind reorganised to form the new British Indian Empire after the British Government abolishes the East India Company | ||

| 1877 | House of Windsor is made the new Imperial Royal Family. Queen Victoria declared the first Emperess of the British Indian Empire | ||

| 1900 | Maghfoor Ahmad Ajazi, the veteran Indian Independence movement activist, is born in Muzaffarpur | ||

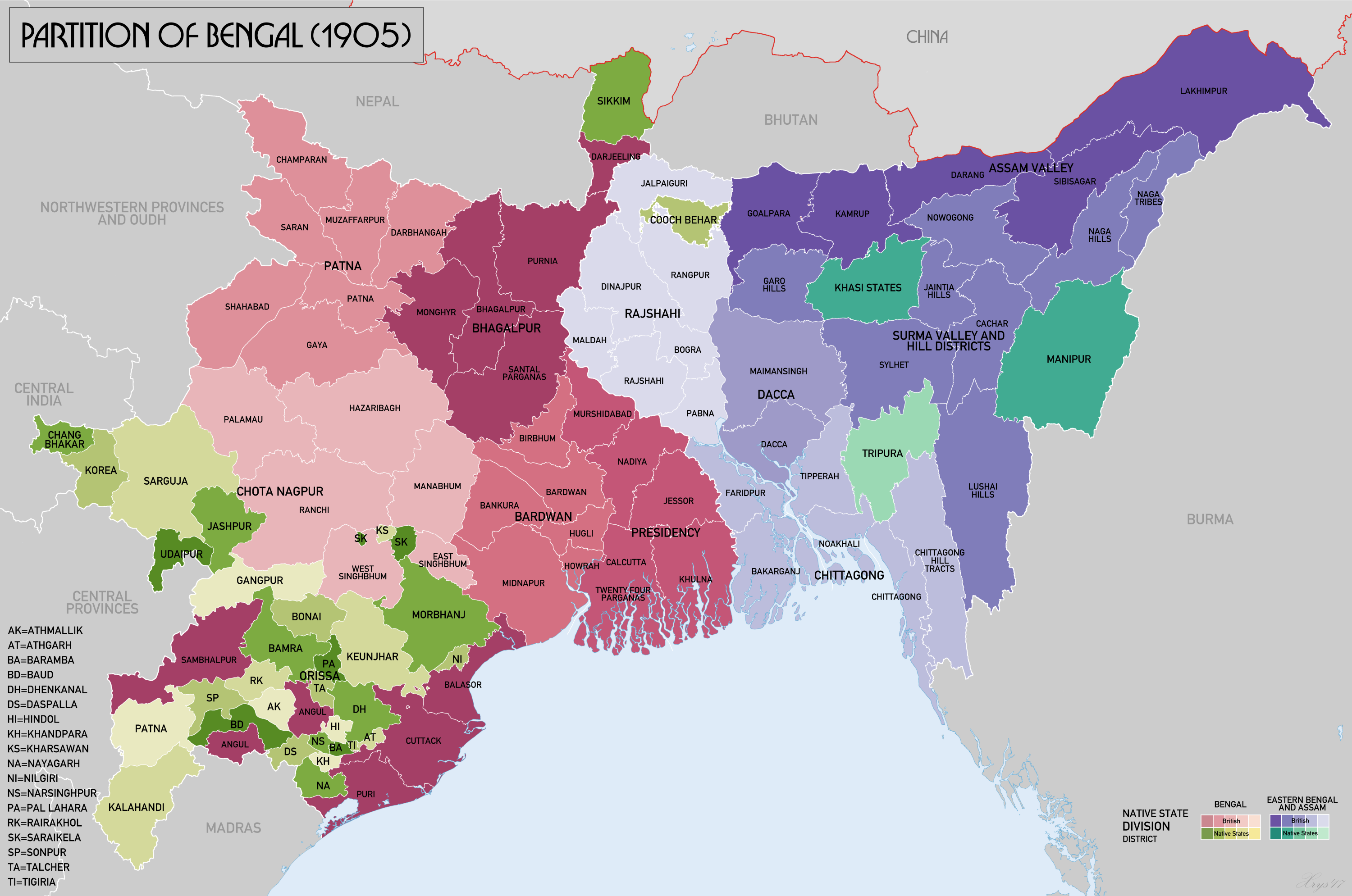

| 1912 | Bihar and Orissa separated from Bengal Presidency | ||

| 1913 | Start of the dramatic slowdown in wealth creation in India and Bihar | ||

| 1916 | Patna High Court founded | ||

| 1917 | Mahatma Gandhi launches Champaran Satyagraha. Establishment of Patna University. | ||

| 1925 | Patna Medical College Hospital was established under the name “Prince of Wales Medical College” | ||

| 1935 | Government of India Act federates the Indian Empire | ||

| 1936 | Bihar gets its first Governor (Sir James David Sifton) | ||

| 1937 | First democratic election in Bihar; Congress emerges as the largest party | ||

| 1940 | The All India Jamhur Muslim League was formed by Maghfoor Ahmad Ajazi to counter the Lahore resolution, passed by the All-India Muslim League, for a separate Pakistan based on Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s Two nation theory. The first session of the party was held at Muzaffarpur in Bihar | ||

| 1942 | Launch of Quit India Movement.Prominent Bihar leaders like Rajendra Prasad, Anugrah Narayan Sinha & Sri Krishna Sinha imprisoned | ||

| 7. Post-Independence | |||

| 1946 | First Cabinet of Bihar formed; consisting of two members, Sri Krishna Sinha as first Chief Minister of Bihar and Dr. Anugrah Narayan Sinha as Bihar’s first Deputy Chief Minister cum Finance Minister (also in charge of Labour, Health, Agriculture and Irrigation). Other ministers are inducted later. The cabinet served as the first Bihar government after independence in 1947 | ||

| 1947 | Indian Independence; Bihar becomes a state in the new Dominion of India | ||

| 1947 – 1949 | Hindu-Muslim religious violence leads to the migration of millions of Bihari Muslims to Pakistan (West and East) | ||

| 1950 | Dr. Rajendra Prasad becomes first President of India | ||

| 1952 | Indian Government adopts symbols related to Bihar (Ashoka Chakra for the Indian flag, the Lion Pillar is made the symbol of the central government of India, all state governments, reserve bank, and the military, whilst the rupee, introduced in the area which is part of modern-day Bihar, is retained as the currency) | ||

| 1952 | State government initiates many irrigation and industrial development projects. It included several river valley projects right from Koshi, Aghaur and Sakri to several other such river projects | ||

| 1952-57 | Purulia became a part of West Bengal state and Bihar ranked best-administered state in India | ||

| 1955 | The Birla Institute of Technology (BIT) is established at Mesra, Ranchi | ||

| 1957 – 1962 | Second five-year plan period, Bihar government brought several heavy industries like Barauni Oil Refinery, HEC plant at Hatia, Bokaro Steel Plant, Barauni Fertiliser Plant, Barauni Thermal Power Station, Maithon Hydel Power Station, Sulphur mines at Amjhaur, Sindri Fertiliser Plant, Kargali Coal Washery, Barauni Dairy Project, etc. for the all round development of the state | ||

| 1974-77 | Bihar leads resistance against Emergency (Suspension of the Republican Constitution. Immediately after proclamation of emergency, prominent opposition political leaders from Bihar like Jayaprakash Narayan & Satyendra Narayan Sinha were arrested without any prior notice. Bihar is the centre of resistance against the Emergency) | ||

| 1977 | Janata Party Came to power at Centre and in Bihar;Karpoori Thakur became CM after winning chief ministership battle from the then Janata Party President Satyendra Narayan Sinha | ||

| 1984 | Indira Gandhi Assassination leads to deadly anti-Sikh Riots in northern India, including Bihar | ||

| 1985 | Pandit Bindeshwari Dubey sworn in as Bihar Chief Minister after Congress’s victory in assembly elections. Kanti thermal power station started operations as the second thermal power plant in Bihar, after Barauni Thermal Power Station, with the help of efforts by the then MP of Muzaffarpur, George Fernandes | ||

| 1988 – 1990 | Removal of Bihar CM Bhagwat Jha Azad, Veteran Leader S N Sinha sworn in as Chief Minister of Bihar, Lalu Prasad Yadav appointed Leader Of Opposition | ||

| 8. Modern Bihar | 1990 – Present | ||

| [8.1] Lalu-Rabri Rule | (1990-2005) | ||

| 1990 | Janata Dal wins the Bihar election, Lalu Prasad becomes Bihar Chief Minister (CM), defeating former Janata Party CM Ram Sundar Das | ||

| 1995 | Janata Dal’s second electoral victory | ||

| 1995-2000 | Economic stagnation, Bihar’s GDP contracts | ||

| 1996 | Lalu Prasad appoints his wife, Rabri Devi, as CM | ||

| 1997 | Split in Janata Dal, Nitish Kumar and Ram Vilas Paswan create Janata Dal (United) | ||

| 1999 | Presidential rule imposed in Bihar because of complete denigration of governance, then lifted because not endorsed by the Rajya Sabha, Rabri Devi back as CM | ||

| 2000 | Bihar is split into Bihar and Jharkhand, by the National Democratic Alliance central government | ||

| 2000 | Lalu Prasad’s split Janata Dal wins elections | ||

| 2000 | Nitish Kumar becomes Bihar CM for seven days, then resigns after his government fails to garner majority. Janata Dal back in power | ||

| 2002-2004 | Deadly crime wave grips Patna and Bihar | ||

| [8.2] Nitish Kumar Era | Post 1997 | ||

| 2005 | In February Lalu Prasad Yadav and Rabri Devi lose power after 15 years | ||

| 2005 | In November, Janata Dal (United) and the BJP win the state election. Nitish Kumar becomes CM, defeating Lalu | ||

| 2007 | Bhojpuri cinema hall complex bombed in Punjab. Six UP and Bihari migrant workers killed | ||

| 2008 | Second Bihari-Bhojpuri Immigrant Worker Crisis: Migrants and students attacked in Maharashtra, Assam, Manipur, and Nagaland. Economic revival Q1 2008, resulting in labour shortages in Punjab, Maharashtra | ||

| 2008 | Floods in Mithla region kill 3,000 people, displace | ||

| 2005 – 2007 | Nitish Kumar is declared the best Chief Minister in India by India Today magazine | ||

| 2010 | Nitish wins again with a historic mandate | ||

| 2014 | Nitish Kumar resigns after the historic debacle in 2014 Lok Sabha elections; Jitan Ram Manjhi is new CM | ||

| 2015 | Nitish Kumar sworn in as Bihar CM for the fourth time after resignation of incumbent Jitan Ram Manjhi | ||

| 2017 | Nitish Kumar becomes CM of Bihar for the record fifth time after spectacular victory of Grand Alliance coalition, Former CM Lalu Prasad Yadav’s younger son Tejashwi Yadav, a debutant MLA, is sworn in as the fourth Deputy Chief Minister of Bihar, becoming the youngest person to hold the post, while the elder son of Lalu Prasad Yadav, Tej Pratap becomes Health Minister |

Neolithic Period (New Stone Age) (10,800–3300 BC)

The earliest evidence of human activity in Bihar is the Mesolithic habitational remains at Munger. Additionally, prehistoric rock paintings have been discovered in the hills of Kaimur, Nawada, and Jamui, depicting the lifestyle and natural environment of early humans. Rock paintings, also referred to as cave paintings, are a form of prehistoric rock art found on cave walls and ceilings. They have been studied extensively since the 1940s and are also known by various names, such as rock carvings, rock engravings, and rock sculptures.

These paintings illustrate the Sun, Moon, stars, animals, plants, trees, and rivers, suggesting a deep connection with nature. They also portray daily activities such as hunting, running, dancing, and walking, providing insights into early human existence in the region. Remarkably, these paintings are not only similar to those found in central and southern India but also resemble prehistoric rock art from Europe and Africa, including the Altamira caves in Spain and Lascaux caves in France.

- Southern India, also known as Peninsular India, is the southern part of the Deccan Peninsula in India encompassing the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana as well as the union territories of Lakshadweep and Puducherry.

- The Cave of Altamira in Spain, discovered in 1868, features charcoal drawings and polychrome paintings of local fauna and human hands from the Upper Paleolithic period (c. 36,000 years ago).

- Similarly, the Lascaux caves in France, containing over 600 paintings, date back to around 17,000–22,000 years ago and are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage sites due to their artistic and historical significance.

Neolithic settlement at Chirand

The Neolithic settlement at Chirand, an archaeological site in the Saran district of Bihar, discovered over the alluvial banks of the Ganges, was significant because it was the first Neolithic site found in an alluvial region. Alluvium, composed of loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel deposited by running water, is known for its high fertility, making it an ideal location for early human settlements and agriculture. This played a crucial role in the development of early civilizations.

Overall, the prehistory of Bihar, as evidenced by Mesolithic remains and rock paintings, contributes significantly to our understanding of early human life in India. The similarities between rock art in Bihar and famous sites in Europe and Africa highlight a shared artistic and cultural tradition among prehistoric humans across different continents.

Bronze Age (3300–1300 BC)

Parallel to the Indus Valley Civilization

The history of Bihar, particularly the ancient city of Vaishali, exhibits certain connections with the Indus Valley Civilization (3300 BCE – 1300 BCE), though definitive research is still lacking. In 2017, bricks dating back to the Mature Harappan period were discovered on the outskirts of Vaishali. This suggests a possible link between the Indus Valley Civilization and Bihar. Additionally, a round seal excavated from Vaishali, dated between 200 BCE and 200 AD, contains three inscribed letters. According to Indus Valley scholar Iravatham Mahadevan, these inscriptions resemble the formulas inscribed on Indus seals, and he dates them to around 1100 BCE, making them potentially among the earliest layers of excavation in Bihar.

The Indus Valley Civilization, a Bronze Age civilization, flourished in the northwestern regions of South Asia, covering parts of modern-day India and Pakistan. It existed from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, reaching its mature phase between 2600 BCE and 1900 BCE. The civilization extended across the Indus River valley in Pakistan and monsoon-fed river systems in northwest India, including the now-seasonal Ghaggar-Hakra River. The Harappan culture, named after its type site Harappa, was first identified in the early 20th century following excavations led by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), founded in 1861 during British rule. The excavation of Harappa, soon followed by the discovery of Mohenjo-daro, marked a turning point in understanding South Asia’s ancient past.

Harappan architecture

Harappan architecture was highly advanced, featuring urban planning, baked brick houses, elaborate drainage and water supply systems, and large non-residential buildings. The civilization also excelled in handicrafts (such as carnelian products and seal carving) and metallurgy (working with copper, bronze, lead, and tin). The major urban centers of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa had estimated populations between 30,000 and 60,000 people, while the entire civilization may have housed between one and five million individuals.

Though substantial evidence of a direct connection between Bihar and the Indus Valley Civilization is yet to be confirmed, findings from Vaishali indicate the possibility of shared influences. As more excavations and research are conducted, the links between early urban settlements in Bihar and the great Bronze Age civilization may become clearer.

Rigvedic Period and the Kingdom of Kikata

The Kikata Kingdom was an ancient region mentioned in the Rigveda, and scholars have debated its precise location. Many believe that the Kikatas were the forefathers of the Magadhas, as the term Kikata is used synonymously with Magadha in later texts. The kingdom is generally thought to have been located south of Magadha in a hilly landscape, possibly around present-day Gaya, Bihar. Some sources describe it as extending from Caran-adri to Gridharakuta (Vulture Peak), near Rajgir.

The Rigveda (RV 3.53.14) refers to the Kikatas as a tribe, and scholars like Weber and Zimmer have placed them in southwestern Bihar (Magadha). However, this is disputed by scholars such as Oldenburg and Hillebrandt. Another argument, put forth by A. N. Chandra, suggests that the Kikatas were located in a hilly part of the Indus Valley, as intermediate regions like Kuru and Kosala are not mentioned.

Religious and Cultural Aspects of the Kikatas

The Kikatas were considered Anarya (non-Vedic people) because they did not practice Vedic rituals like soma sacrifices. According to Sayana, they did not perform worship, were infidels, and were Nastikas (deniers of Vedic traditions). The leader of the Kikatas was Pramaganda, who is described as a usurer. It is uncertain whether the Kikatas originally lived in Magadha during the Rigvedic period or migrated there later.

Similar to the Rigvedic descriptions of the Kikatas, the Atharvaveda also refers to southeastern tribes like Magadhas and Angas as hostile groups who lived on the periphery of Brahmanical India. The Bhagavata Purana even mentions that Buddha was born among the Kikatas, possibly indicating an early non-Vedic tradition in the region.

Scholarly Debate on the Location of Kikata

While some scholars place the Kikata Kingdom in Bihar (Magadha) due to later textual references, others challenge this identification. Michael Witzel suggests that Kikata was located south of Kurukshetra, in eastern Rajasthan or western Madhya Pradesh. Additionally, Mithila Sharan Pandey argues that the Kikatas must have been near western Uttar Pradesh, while O.P. Bharadwaj places them near the Sarasvati River. Historian Ram Sharan Sharma believes that they were probably in Haryana.

Despite these varying opinions, the association of Kikata with Magadha in later texts suggests that, at some point, the region may have become culturally or politically linked to Magadha. However, further archaeological and textual research is needed to establish a definitive connection.

Urbanization in the Gangetic Plains and the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW)

The urbanization of the Gangetic plains began with the emergence of the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) period, which is widely regarded as a marker of the second phase of urbanization in ancient India. Archaeologists trace the origin of this pottery to the Magadha region of Bihar, indicating that this region played a pivotal role in the early development of urban settlements.

The oldest dated site of NBPW has been discovered in Juafardih, Nalanda, Bihar, and it has been carbon-dated to around 1200 BCE. This suggests that the Magadha region was among the earliest centers of urban culture in the Gangetic plains.

NBPW is characterized by its fine, glossy, and highly burnished pottery, which is typically black or deep grey in color. This type of pottery is associated with early urban settlements, economic expansion, and the rise of powerful kingdoms, particularly Magadha. The presence of NBPW in Magadha aligns with historical accounts that describe the region as a center of power, trade, and cultural development.

The spread of NBPW across northern India—including regions like the Doab, Bengal, and the Deccan—suggests the increasing influence of Magadha and the development of a complex socio-economic structure. This period also coincides with the rise of the Mahajanapadas (large kingdoms) and the expansion of political and economic networks in ancient India.

Iron Age (1500–200 BC)

Late Vedic Kingdoms

Mithila and The Videha Kingdom

The Videha Kingdom, also known as Mithila, was an important Indo-Aryan kingdom in the north-eastern Indian subcontinent during the Iron Age. It is mentioned in both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, as well as in various Vedic texts. The kingdom covered parts of present-day Bihar (India) and Nepal.

Geography and Boundaries:

The kingdom of Videha was strategically located between major rivers and natural boundaries:

- Sadānirā River (Gandak) – Western border

- Kauśikī River (Kosi) – Eastern border

- Gaṅgā River – Southern border

- Himalayas – Northern border

To the west of the Sadānirā River, Videha’s neighbor was the powerful kingdom of Kosala. The region covered what is now the Tarāī area of Nepal and the northern parts of Bihar, India.

Political Evolution: From Monarchy to Republic

Initially, the Vaidehas, the people of Videha, were organized as a monarchy under a series of kings known as the Janakas. The most famous of these kings was Raja Janaka, the father of Goddess Sita, the consort of Lord Rama in the Ramayana.

Later, the monarchy transitioned into a republic (gaṇasaṅgha), forming what is now referred to as the Videha Republic. This republic became part of the Vajjika League, a confederation of states that also included the Lichchhavis and Mallas. The neighboring Malla republics were located west of the Sadānirā River.

Capital of Videha:

The capital of the Videha Kingdom was Mithilā, named after the Vaideha king Mithi. However, ancient texts mention different names for the capital:

- Jayantapura – Mentioned in the Vāyu Purāṇa, said to have been founded by King Nimi.

- Vaijanta – Referred to in the Bāla Kāṇḍa of Vālmīki’s Rāmāyaṇa.

- Janakpur (present-day Nepal) or Baliraajgadh (Madhubani district, Bihar, India) – These are modern sites identified as possible locations of ancient Mithilā.

Cultural and Historical Significance:

- Videha was a major center of learning, philosophy, and spirituality in ancient India.

- Janaka’s court was known for intellectual debates and hosted philosophers like Yājñavalkya.

- The kingdom played a crucial role in the development of Vedic traditions and Hindu epics.

The transformation of Videha from a monarchy to a republic and its inclusion in the Vajjika League highlights the political evolution that took place in ancient India.

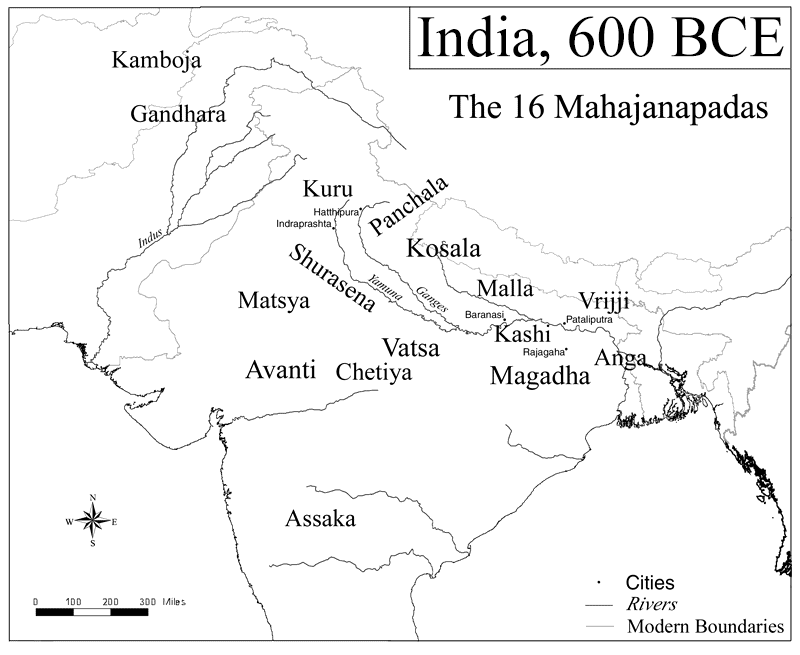

The Anga Kingdom

The Anga Kingdom was an ancient Indo-Aryan kingdom located in eastern India, present in historical records from the Iron Age. While some sources suggest that Anga was initially non-Vedic and later captured by the Vedic Aryans, other legends claim that Prince Anga was its first Vedic king, after whom the kingdom was named.

Geographical Location and Boundaries:

The Anga Kingdom was strategically positioned between important geographical landmarks:

- Champā River – Western boundary

- Rajmahal Hills – Eastern boundary

- The sea (at times) – Southern extension

- Magadha (sometimes included within Anga’s domain) – Western boundary

Anga was a powerful kingdom during the early Vedic period, but with the rise of Magadha and Vaishali, it gradually lost prominence.

Capital and Important Cities:

The capital of Anga was Campā, located at the confluence of the Campā and Gaṅgā rivers. Today, this corresponds to Campāpurī and Champanagar in Bhagalpur, Bihar. Ancient texts mention different names for the capital:

- Kāla-Campā – Mentioned in the Jātakas

- Mālinī – Referred to in Puranic texts

Other important cities within the kingdom included:

- Assapura (Aśvapura)

- Bhaddiya (Bhadrika)

Mythological and Historical Origins:

According to the Mahabharata and Puranic literature, the kingdom of Anga was named after Prince Anga, son of King Vali. The legend states that Vali, having no sons, sought the blessing of the sage Dirghatamas, who fathered five sons through Vali’s wife Sudesna:

- Aṅga

- Vaṅga

- Kaliṅga

- Sumha

- Pundra

These sons later founded their respective kingdoms. The Ramayana also provides a different explanation for the name Aṅga, linking it to the location where Kamadeva (God of Love) was burned to ashes by Lord Shiva, and where his body parts (aṅgas) were scattered.

Mention in Vedic and Buddhist Texts:

- The Atharvaveda is the first Vedic text to mention Anga, associating it with Gāndhārīs, Mūjavats, and Māgadhīs.

- The Aitareya Brāhmaṇa names King Anga Vairocana as the first ruler of Anga to undergo the Aindra mahābhiśeka (a Vedic Aryan coronation ritual).

- Buddhist texts, such as the Aṅguttara Nikāya, list Anga among the sixteen great Mahājanapadas (major states of ancient India).

- Jain texts, like the Vyākhyāprajñapti, also recognize Anga as a significant janapada.

Political Power and Expansion:

Anga was a dominant kingdom during the period of the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, with some kings conducting world conquests. The capital Campā remained a major trade and political center until the death of the Buddha.

During the Iron Age, Anga expanded to include Vaṅga within its territory. The capital Campā became a rich commercial hub, sending traders to Suvarṇabhūmi (Southeast Asia). Viṭaṅkapura, another Anga city, was mentioned as being on the sea coast in the Kathā-sarit-sāgara.

Relations with Other Kingdoms:

During the 6th century BCE, King Dadhivāhana ruled Anga. His wife, Padmāvatī, was a Licchavika princess, making him related to Ceṭaka, the powerful Licchavika leader and uncle of Mahāvīra, the 24th Jain Tīrthaṅkara. This helped spread Jainism across northern India.

Conquests and Conflicts:

- Dadhivāhana conquered Magadha, making its capital Rājagaha a part of Anga (as per the Vidhura Paṇḍita Jātaka).

- Vatsa’s King Śatānīka feared Anga’s expansion and attacked Campā. However, Dadhivāhana preferred diplomacy and married his daughter to Śatānīka’s son, Udayana.

- Later, Kaliṅga attacked Anga and took Dadhivāhana captive. After Udayana was freed from Avanti’s King Pradyota, he defeated Kaliṅga and restored Dadhivāhana to the throne.

- Dadhivāhana’s daughter, Priyadarśikā, later married Udayana.

Decline and Annexation by Magadha:

Anga’s prosperity ended in the mid-6th century BCE when Bimbisāra of Magadha avenged his father’s defeat by attacking Anga. King Brahmadatta of Anga was killed, and Anga was annexed into the Magadhan Empire. Campā became the seat of a Magadhan viceroy, marking the end of Anga’s independence.

Despite its decline, Anga remained an important cultural and economic center. It played a crucial role in early Jainism and Buddhism and contributed significantly to the trade networks of ancient India.

The Magadha Kingdom

Origins and Mythological Foundation:

The Magadha Kingdom was established by King Jarasandha, a semi-mythical ruler belonging to the Brihadratha dynasty. According to the Puranas, Jarasandha was a descendant of King Puru, the legendary son of King Yayati and Sharmishtha. Puru was the ancestor of both the Pandavas and Kauravas. His lineage continued through Janamejeya, his successor.

The Puranas, a vast genre of ancient Indian literature, document legends and traditional lore associated with Hinduism and Jainism. Many of these texts are named after major Hindu deities such as Vishnu, Shiva, and Brahma.

Jarasandha and the Brihadratha Dynasty:

Jarasandha, one of the most powerful rulers of Magadha, appears in the Mahabharata and Vayu Purana. He was a significant antagonist in the epic, described as the “Magadhan Emperor who ruled all of India.” His capital, Rajagriha (modern Rajgir, Bihar), was a strategic and influential city.

Jarasandha’s continuous assaults on the Yadava kingdom of Surasena forced the Yadavas to migrate westward. His dominance was a threat not only to the Yadavas but also to the Kurus. Ultimately, he was killed in a mace duel by Bhima, aided by Krishna’s strategic intelligence. His death allowed Yudhishthira to complete his campaign to bring the entire Indian subcontinent under his rule.

According to the Vayu Purana, the Brihadratha dynasty ruled Magadha for 1000 years, followed by the Pradyota dynasty (799–684 BCE). However, there is insufficient historical evidence to validate this claim.

Magadha’s Geographical Significance:

Magadha was one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas and played a crucial role in India’s Second Urbanization period. The kingdom was strategically positioned in eastern India, bound by:

- North: Gaṅgā River

- West: Son River

- East: Campā River

- South: Vindhya Mountains

This territory corresponded to modern-day Patna and Gaya districts of Bihar. As Magadha expanded, it absorbed many neighboring regions, forming the Greater Magadha region.

Rise of the Mahajanapadas and Religious Influence:

During the later Vedic Age, India was composed of small kingdoms and city-states. By 500 BCE, sixteen major kingdoms or Mahajanapadas emerged, including Kasi, Kosala, Anga, Magadha, Vajji, Malla, Chedi, Vatsa, Kuru, Panchala, Matsya, Surasena, Assaka, Avanti, Gandhara, and Kamboja.

By 400 BCE, four dominant Mahajanapadas remained: Vatsa, Avanti, Kosala, and Magadha. Magadha played a key role in the rise of Jainism and Buddhism:

- Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha) attained enlightenment in 537 BCE at Bodh Gaya, Bihar.

- Mahavira, the 24th Jain Tirthankara, was born in Vaishali (ancient Bihar) and spread Jain teachings.

- Nalanda and Vikramshila Universities, major centers of learning, were established in Bihar.

Both religions rejected Vedic rituals, promoted ahimsa (non-violence), and influenced Hinduism, particularly in practices like vegetarianism.

The Pradyota and Shishunaga Dynasties:

The Pradyota dynasty (799–684 BCE) followed the Brihadrathas. Pradyota rulers were known for violent succession traditions, where a king’s son would assassinate his father to gain power. This era saw high crime rates, leading to civil unrest.

In 684 BCE, the people overthrew the Pradyota dynasty and elected Shishunaga as king, founding the Shishunaga dynasty. This new empire initially had its capital at Rajgriha before shifting to Pataliputra (modern Patna). The Shishunaga dynasty became one of the largest empires in India.

The Haryanka Dynasty (543–413 BCE):

The Haryanka dynasty was founded by Bimbisara. He expanded Magadha through conquests and matrimonial alliances, notably acquiring Kosala through marriage. Under his rule, the empire grew significantly.

Bimbisara was a contemporary of Gautama Buddha and became a lay disciple of Buddhism. However, his rule ended when his son, Ajatashatru (491–461 BCE), imprisoned and killed him to ascend the throne. Ajatashatru moved the capital from Rajagriha to Pataliputra, which became a major political and cultural center.

Ajatashatru frequently clashed with the Licchavis, whose capital, Vaishali, was prosperous due to figures like the courtesan Ambapali. His successors faced violent successions, with each ruler assassinating his predecessor.

The Nanda Dynasty (424–321 BCE):

The Nanda dynasty succeeded the Shishunagas. It was established by an illegitimate son of King Mahanandin. The Nandas built a vast empire that extended from Burma to Balochistan and possibly Karnataka.

The most powerful Nanda ruler, Mahapadma Nanda, was called the “destroyer of all Kshatriyas” and conquered many regions, including Kalinga and the Deccan. His son, Dhana Nanda, was the last Nanda ruler, overthrown by Chandragupta Maurya in 321 BCE.

The Maurya Empire (321–185 BCE):

With the help of Chanakya, Chandragupta Maurya established the Maurya dynasty, forming the first pan-Indian empire. The Maurya Empire expanded beyond India, defeating Greek satraps left by Alexander the Great and annexing Balochistan and Afghanistan.

Chandragupta’s son, Bindusara, extended the empire further into central and southern India. His successor, Ashoka the Great, initially expanded through war but later embraced Buddhism after the Kalinga War (261 BCE). The war’s devastation led him to renounce violence and adopt a policy of Dharma (righteous rule), as recorded in his Edicts:

“Beloved-of-the-Gods [Ashoka], King Priyadarsi, conquered the Kalingas eight years after his coronation. 150,000 were deported, 100,000 were killed and many more died. After the Kalingas had been conquered, Beloved-of-the-Gods felt deep remorse and developed a strong inclination toward Dharma.”

Under Ashoka, Buddhism spread across Asia, influencing Sri Lanka, Tibet, Central Asia, China, and Southeast Asia. His Lion Capital at Sarnath remains India’s national emblem today.

Decline of the Maurya Empire:

After Ashoka, weaker rulers governed Magadha for 50 years. The last Mauryan king, Brihadrata, ruled a shrinking empire but maintained Buddhist ideals. Eventually, he was assassinated, leading to the rise of new dynasties.

Magadha played a pivotal role in shaping Indian history, politics, and religion. It fostered the growth of Buddhism and Jainism, established India’s first great empire, and set the foundation for future dynasties. Its legacy continues to influence Indian culture, philosophy, and governance.

Middle Kingdoms (230 BC – 1206 AD)

Shunga Dynasty (187 BCE – 73 BCE)

Establishment of the Shunga Dynasty (185 BCE):

The Shunga dynasty was established in 185 BCE, about fifty years after the death of Emperor Ashoka. The last Mauryan ruler, Brihadratha Maurya, was assassinated by his commander-in-chief, Pushyamitra Shunga, during a military review. Following the assassination, Pushyamitra, a Brahmin, ascended the throne and founded the Shunga dynasty.

Religious and Political Context:

Buddhist texts like the Ashokavadana suggest that the rise of the Shunga Empire led to a persecution of Buddhists and a resurgence of Hinduism. Some historians, such as John Marshall, Etienne Lamotte, and Romila Thapar, support this claim, though others argue that later Shunga rulers were more tolerant toward Buddhism.

Extent of the Shunga Empire:

The Shunga Empire was centered around Magadha and controlled most of northern India from 187 BCE to 75 BCE. The capital was Pataliputra, but later rulers, such as Bhagabhadra, also held court in Besnagar (modern Vidisha) in eastern Malwa. The empire successfully resisted Greek invasions in the Shunga-Greek War.

Rulers and Administration:

- Pushyamitra Shunga (187–151 BCE): The founder of the dynasty, he ruled for 36 years and successfully defended the empire from Indo-Greek incursions.

- Agnimitra (151–141 BCE): Pushyamitra’s son, he was previously the viceroy of Vidisha. He is the hero of Kālidāsa’s play Malavikagnimitra.

- Successive rulers: There were ten Shunga rulers, but after Agnimitra, the empire gradually disintegrated into small kingdoms and city-states.

- Devabhuti (83–73 BCE): The last Shunga emperor, he was assassinated by his minister, Vasudeva Kanva, leading to the rise of the Kanva dynasty around 73 BCE.

Military Conflicts and Foreign Relations:

The Shungas engaged in numerous wars against both foreign and indigenous powers, including:

- Kalinga

- Satavahanas

- Indo-Greeks

- Panchalas and Mitras of Mathura (possibly)

Some historical sources claim that Pushyamitra persecuted Buddhist monks as far as Sakala (Sialkot, Punjab), while others suggest that the Shungas controlled territories up to the Narmada River in the south. However, the Indo-Greeks controlled Mathura during much of this period, as seen in the Yavanarajya inscription.

Cultural Contributions and Legacy:

Despite political instability, art, education, and philosophy flourished during the Shunga period. Notable achievements include:

- The construction of the Great Stupa at Sanchi and the Stupa at Bharhut.

- Terracotta images and stone sculptures that influenced later Indian art styles.

- Patanjali’s Mahābhāṣya, an important Sanskrit grammar text, was composed.

- The development of the Mathura art style.

- The use of a variant of the Brahmi script to write Sanskrit.

Uncertainty Over the Name “Shunga”:

The name “Shunga” is primarily used as a historical designation, but epigraphic evidence is limited. The Bharhut inscription refers to a dedication made “during the rule of the Suga kings,” which could alternatively refer to the Sughanas, a northern Buddhist kingdom. Other inscriptions, like the Heliodorus pillar, are only assumed to relate to Shunga rulers.

The Vishnu Purana, an ancient Hindu text, mentions the Shunga lineage, listing ten kings from Pushyamitra to Devabhuti, ruling for 112 years.

Decline and Fall of the Shunga Dynasty (73 BCE):

The power of the Shungas gradually declined, and by 73 BCE, the last emperor Devabhuti was assassinated by Vasudeva Kanva, leading to the establishment of the Kanva dynasty.

Gupta Dynasty (c. 240 – 579 CE)

Foundation and Early Rulers:

The Gupta dynasty was established around 240 CE. The first known ruler, Gupta, was succeeded by his son Ghatotkacha (c. 280–319 CE). His successor, Chandra Gupta I, significantly expanded Gupta power through a strategic marriage alliance with the Lichchhavis, the dominant power in Magadha.

Expansion Under Samudragupta (335–380 CE):

Chandra Gupta I was succeeded by his son Samudragupta, who ruled for 45 years (335–380 CE). He launched extensive military campaigns, conquering over twenty kingdoms, including:

- Shichchhatra

- Padmavati

- Malwas

- Yaudheyas

- Arjunayanas

- Maduras

- Abhiras

His empire extended from the Himalayas to the Narmada River and from the Brahmaputra to the Yamuna. He assumed the titles “King of Kings” and “World Monarch” and is often referred to as the “Napoleon of India”. To commemorate his conquests, he performed the Ashwamedha Yajna (horse sacrifice).

Peak of the Gupta Empire Under Chandragupta II (Vikramaditya) (380–413 CE):

Samudragupta was succeeded by his son Chandragupta II, also known as Vikramaditya (Sun of Power). He:

- Expanded the empire westward, defeating the Saka Western Kshatrapas of Malwa, Gujarat, and Saurashtra in a campaign that lasted until 409 CE.

- Promoted trade and prosperity, making the Gupta Empire one of the largest political and military powers of its time.

His successor, Kumaragupta I (r. 413–455 CE), ruled successfully until the rise of the Pushyamitras, a tribe in the Narmada valley, threatened the empire.

Decline of the Gupta Empire:

The last great Gupta ruler was Skandagupta (r. 455–467 CE), who:

- Defeated the Pushyamitra rebellion.

- Successfully repelled an invasion by the Hephthalites (Hunas) around 477 CE.

However, after Skandagupta’s death in 487 CE, the empire weakened due to continuous Huna invasions. His successor, Narasimhagupta Baladitya, was unable to prevent further decline, and by 579 CE, the empire had fragmented into smaller regional kingdoms.

Administration and Governance:

The Gupta administration differed from the centralized Mauryan model:

- Decentralized governance: Power was distributed among provinces, which were divided into districts and villages (the smallest administrative units).

- Capital at Pataliputra (modern Patna).

- Sanskrit became the official language, used in government, religious, and cultural practices.

Golden Age of Art, Science, and Literature:

The Gupta period is considered the “Classical Age” of India, marked by great achievements in:

Astronomy and Mathematics:

- Aryabhata:

- Introduced the concept of zero.

- Stated that Earth rotates on its axis and moves around the Sun.

- Studied solar and lunar eclipses.

- Wrote the famous Aryabhatiya.

- Varahamihira:

- Authored the Brihat-Samhita and Pancha-Siddhantika.

- Advances in metallurgy led to the creation of the Iron Pillar of Mehrauli (Delhi).

Sanskrit Literature:

- Kalidasa’s works:

- Raghuvamsa

- Malavikagnimitram

- Meghadūta

- Abhijñānaśākuntala

- Kumārasambhava

- Other literary works:

- Mṛcchakatika by Shudraka.

- Panchatantra by Vishnu Sharma.

- Kama Sutra by Vatsyayana.

- 13 plays by Bhasa.

Medicine:

- Ayurveda was the dominant medical system.

- Gupta doctors excelled in:

- Pharmacopoeia

- Caesarean section

- Bone setting

- Skin grafting

- Gupta medical knowledge later influenced Arab and Western medicine.

Economic Prosperity and Coinage:

- The Guptas issued a large number of gold coins called dinars, featuring inscriptions of rulers.

- Trade flourished both within India and with regions such as Persia, Southeast Asia, and the Roman Empire.

Fall of the Gupta Empire:

The Gupta Empire faced repeated Huna invasions, which weakened central authority. Over time:

- Decentralized administration made it difficult to mobilize resources against external threats.

- The empire broke into smaller regional kingdoms by 579 CE, marking the end of Gupta rule.

Later Gupta Dynasty (6th–7th Century CE)

Origins and Distinction from the Imperial Guptas:

The Later Gupta dynasty ruled Magadha in eastern India between the 6th and 7th centuries CE. Although their name suggests continuity with the Imperial Gupta Empire, there is no direct evidence connecting the two dynasties. Historians believe the Later Guptas adopted the “-gupta” suffix to establish legitimacy by associating themselves with the renowned Imperial Guptas.

Sources of Historical Information:

The primary sources providing information about the Later Gupta dynasty include:

- Aphsad inscription of Ādityasena (records the genealogy from Kṛṣṇagupta to Ādityasena).

- Deo Baranark inscription of Jīvitagupta II.

- Harshacharita by Bāṇabhaṭṭa (mentions Later Gupta rulers).

- Chinese pilgrims Xuanzang and Yijing (document the period).

- Gaudavaho of Vākpatirāja, which refers to the victory of Yashovarman of Kannauj over Jīvitagupta II.

Territorial Expansion and Governance:

- The Later Guptas originated in Magadha (modern Bihar), where all their inscriptions have been found.

- A Nepalese inscription refers to King Ādityasena as “Lord of Magadha”.

- Initially feudatories of the Imperial Guptas, they gained power after the fall of the Empire.

Rulers of the Later Gupta Dynasty

Kṛṣṇagupta (Founder, c. 6th century CE):

- Established the Later Gupta dynasty after the decline of the Imperial Guptas.

- His daughter married Adityavarman of the Maukhari dynasty, forming a strategic alliance.

Jīvitagupta I (Grandson of Kṛṣṇagupta, c. 6th century CE):

- Conducted military campaigns in the Himalayan region and southwestern Bengal.

Kumaragupta (Son of Jīvitagupta I, ruled c. 554 CE):

- Defeated the Maukhari king Ishanavarman in 554 CE.

- Expanded his rule to Prayaga (modern Prayagraj).

Damodaragupta (Son of Kumaragupta, c. late 6th century CE)

- Suffered defeats against the Maukharis and was pushed back into Magadha.

Mahasenagupta (Son of Damodaragupta, ruled c. 562–601 CE):

- Formed an alliance with the Pushyabhuti dynasty.

- His sister married Adityavardhana, a Pushyabhuti ruler.

- Conducted a successful invasion of Kamarupa, defeating Susthita Varman.

- Later faced three major invaders:

- Sharvavarman (Maukhari king)

- Supratishthita-Varman (Kamarupa king)

- Songtsen Gampo (Tibetan king)

- His vassal Shashanka abandoned him and later founded the Gauda Kingdom.

- Defeated by Sharvavarman of the Maukharis (c. 575 CE), which forced him to flee to Malwa.

- The Later Gupta rule in Magadha was temporarily restored by Harsha (Pushyabhuti dynasty, ruled c. 606–647 CE).

Ādityasena (Later Gupta ruler after Harsha’s death, ruled c. 7th century CE):

- Became an independent sovereign ruler after Harsha’s death.

- His kingdom extended:

- From the Ganges (north) to Chhota Nagpur (south).

- From the Gomati River (west) to the Bay of Bengal (east).

- Defeated by the Chalukyas.

Jīvitagupta II (Last known ruler, ruled c. 750 CE):

- Defeated by Yashovarman of the Varman dynasty of Kannauj (c. 750 CE).

- Marked the end of the Later Gupta dynasty as a significant power.

Coinage and Religious Influence:

- The Later Gupta coinage is scarce, with most coins found from Mahasenagupta’s reign (562–601 CE).

- Distinct features of Later Gupta coins:

- Depictions of Nandi (sacred bull of Shiva) replaced the Garuda symbol used by the Imperial Guptas.

- Two major types: “Archer type” and “Swordsman type” coins.

- The Later Guptas were devout Shaivites, as seen from their coinage and inscriptions.

Possible Continuation of the Dynasty:

- A small kingdom in the Lakhisarai district (11th–12th century CE) bore the Gupta name.

- Panchob copper-plate inscription (discovered in 1919) suggests that a branch of the Later Guptas survived in the region.

Pala Dynasty (750–1120 CE)

Origins and Establishment:

The Pala Empire was a Buddhist dynasty that ruled over Bengal and Bihar in the Indian subcontinent. The word “Pala” (Modern Bengali: পাল, pal) means “protector” and was used as a suffix in the names of all Pala monarchs.

- Gopala (750–770 CE) was the first ruler and came to power in 750 CE through a democratic election in Gaur.

- This event is considered one of the earliest instances of democratic elections in South Asia since the time of the Mahā Janapadas.

- Gopala unified Bengal and extended his rule into Bihar, laying the foundation of the dynasty.

Expansion and Peak of the Empire:

The Pala Empire reached its zenith under Dharmapala and Devapala, who expanded its territorial reach across a vast portion of the Indian subcontinent.

Dharmapala (770–810 CE):

- Extended the empire into northern India, engaging in power struggles with the Pratiharas and Rashtrakutas.

- Patronized Nalanda and Vikramashila Universities, making them international centers of Buddhist learning.

- Strengthened Buddhist influence in India and beyond, supporting the Mahayana and Tantric schools of Buddhism.

Devapala (810–850 CE):

- Expanded the empire to its greatest territorial extent, covering:

- Assam and Odisha (Utkala) in the east.

- Kamboja (modern Afghanistan) in the northwest.

- The Deccan in the south.

- According to Pala copperplate inscriptions, Devapala:

- Defeated the Utkalas and Pragjyotisha (Assam).

- Crushed the Hunas and humbled the Gurjara-Pratiharas.

- Subdued the Dravidas (South Indian rulers).

- Capital at Pataliputra (modern Patna) during his reign.

Cultural and Educational Contributions:

- The Palas were great patrons of Buddhism, art, and education.

- They built many temples and stupas, including:

- Somapura Mahavihara (now in Bangladesh) – one of the largest Buddhist monasteries of the time.

- The universities of Nalanda and Vikramashila flourished, attracting students from across Asia.

Decline and Fall:

- By the 11th century, the Pala Empire weakened due to internal conflicts and external invasions.

- Invasions by Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty from South India further weakened the empire.

- The Sena dynasty eventually defeated the Palas in the 12th century, bringing an end to their rule.

Medieval Period (1206–1526)

Fragmentation and Foreign Aggression:

- During the medieval period, Bihar was ruled by various small kingdoms and principalities, leading to political instability.

- The region witnessed its first encounters with foreign invasions, particularly from Muslim armies from the West.

- Muhammad of Ghor launched multiple attacks on Bihar, weakening local rulers and destabilizing the region.

Destruction of Buddhist Heritage:

- The final blow to Buddhism in Magadha came with the invasion of Muhammad Bin Bakhtiyar Khilji in the 12th century.

- Khilji, a general of Qutb-ud-Din Aibak, destroyed Buddhist monasteries and fortified Sena strongholds.

- The famed universities of Nalanda and Vikramshila were reduced to ruins, and thousands of Buddhist monks were massacred.

Survival of Autonomy in North Bihar (Mithila):

- Despite widespread destruction, North Bihar (Mithila) maintained relative autonomy longer than the rest of Bihar.

- The region remained under native dynasties until the 16th century, preserving its distinct cultural and administrative identity.

Karnat Dynasty of Mithila (1097-1324 CE)

Origins and Establishment (1097 CE):

The Karnat dynasty of Mithila was founded in 1097 CE by Nanyadeva, a military commander of Karnataka origin. He initially arrived in 1093 CE and established his stronghold in Nanapura, Champaran, before shifting his capital to Simraungadh, located on the India-Nepal border. His ancestors were likely petty chieftains and adventurers who migrated to Eastern India, initially working under the Pala Empire. Taking advantage of the weakened Pala rule following the Varendra rebellion, Nanyadeva declared independence and established Mithila as an autonomous kingdom.

An inscribed stone pillar at Simraungadh confirms Nanyadeva’s reign with a record dated 10 July 1097 CE (Śaka year 1019), marking the foundation of his rule in Mithila.

Political and Military Expansion:

Nanyadeva extended his influence through military campaigns. He likely had ties with the Chalukya king Vikramaditya VI and fought against the Pala Empire and Sena dynasty. He may have also intervened in Nepalese politics by supporting Śivadeva, a prince of the Thakuri dynasty, in his bid for the throne. This allowed Nanyadeva to establish nominal suzerainty over Nepal, although its exact nature remains uncertain.

However, Nanyadeva faced resistance from Vijayasena, the ruler of the Sena dynasty. The Deopara inscription suggests that Vijayasena defeated Nanyadeva, although Mithila remained independent. Later, Yashahkarna of the Kalachuri dynasty attempted to reclaim parts of Mithila, but his invasion around 1122 CE was ultimately unsuccessful.

Rise of the Karnats and Development of Maithili Culture:

The Karnats ruled Mithila autonomously from 1097 to 1324 CE, referring to themselves as Mithileśwara (Lords of Mithila). Under their reign, Maithili culture flourished, and the first recorded Maithili literary work, Varna Ratnakara, was composed in the 14th century by Jyotirishwar Thakur.

During Gangadeva’s reign, Mithila enjoyed political stability, allowing him to introduce internal reforms, including the Pargana system for revenue collection. He also shifted the capital to Darbhanga, which became an important cultural and administrative center.

Expansion and Conflicts (12th-13th Century):

- Gangadeva (r. after 1147 CE) expanded his influence in Bengal, where he fought against Madanapala of the Gauda region. However, following Madanapala’s death, the Sena dynasty rose to power, and it remains unclear whether Gangadeva engaged in battles with Vijayasena and his successors.

- His successor, Narsimhadeva (r. 1188 CE), faced significant territorial losses to the Sena dynasty in the east, particularly in Purnea. He also likely lost control over Nepal, as Arimalla of the Malla dynasty asserted independence.

- Historical records suggest that Narsimhadeva may have allied with Muhammad of Ghor during his conquest of Delhi in 1193 CE, although there is no evidence that Mithila was subjugated by the Delhi Sultanate.

Decline and Fall (1295-1324 CE):

The last Karnat ruler, Harisimhadeva (r. 1295-1324 CE), faced growing threats from the Tughlaq dynasty. In 1324 CE, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq, the founder of the Tughlaq dynasty, launched a campaign into Bengal. On his return, he turned his attention to Simraungadh, which was flourishing as a fortified capital inside dense forests.

Rather than resisting, Harisimhadeva abandoned the fort and fled northward into Nepal. The Tughlaq army razed Simraungadh, dismantling its massive fortifications and bringing an end to the Karnat dynasty’s rule in Mithila.

Harisimhadeva’s son, Jagatsinghadeva, later married Nayak Devi, the widowed princess of Bhaktapur in Nepal, marking a continued but diminished Karnat presence in Nepalese history.

Legacy of the Karnat Dynasty:

- The Karnat dynasty was the first indigenous dynasty to rule Mithila independently after centuries of control by larger empires like the Palas and Senas.

- They preserved and nurtured Maithili culture, laying the foundation for later literary and linguistic developments.

- Their fortifications at Simraungadh and Darbhanga symbolized their political strength and administrative capabilities.

- Their rule ended with Harisimhadeva’s flight to Nepal, but remnants of their architectural and cultural influence still exist in the Mithila and Simraungadh regions.

The Oiniwar Dynasty (1325-1526)

The Oiniwar dynasty, also known as the Sugauna dynasty, ruled the Mithila region from 1325 to 1526 following the fall of the Karnat dynasty. Unlike their predecessors, the Oiniwars operated from various villages rather than a large citadel. They governed Mithila as vassals of the Delhi Sultanate but maintained significant autonomy. The dynasty played a crucial role in the patronage of Maithili culture, language, and literature and was contemporaneous with the Jaunpur Sultanate.

Origins and Establishment (1325 CE):

The Oiniwars were a Maithil Brahmin dynasty, tracing their lineage to Nath Thakur, a scholar who served the Karnat rulers and was granted the village of Oini in present-day Madhubani district. His family took the name of the village, leading to the Oiniwar title. Some theories suggest they were renowned scholars and were also known as the Srotiyas or Soit.

After the collapse of the Karnat dynasty in 1324, Nath Thakur established himself as the first ruler of the Oiniwar dynasty in 1325. The dynasty consisted of 20 rulers and governed for over two centuries.

Capitals and Political Structure:

Unlike the Karnats, who ruled from Simraungadh, the Oiniwar rulers frequently relocated their capitals.

- Initially, the capital was at Oini, then moved to Sugauna in Madhubani district, leading to the dynasty being called the Sugauna dynasty.

- During Devasimha’s reign, the capital was relocated to Devakuli.

- Shiva Simha Singh moved the capital to Gajarathpura (Shiva Singhpura).

- After Shiva Simha Singh’s death in 1416, his widow Queen Lakshima ruled for 12 years.

- Padmasimha, his successor, shifted the capital to Padma, near Rajnagar.

- His widow, Vivasa Devi, moved it to Vishual.

These frequent shifts led to new infrastructure, including roads, temples, ponds, and forts.

Prominent Rulers and Key Events:

Shiva Simha Singh and Military Strength (Reign: Late 14th – Early 15th Century)

One of the most notable rulers was Shiva Simha Singh, known for his military campaigns and patronage of Maithili culture. He attempted to revolt against the Delhi Sultanate, but his efforts were ultimately unsuccessful.

- The Oiniwar military was structured into four divisions: infantry, cavalry, elephants, and chariots.

- The senapati (commander-in-chief) led the army, with warriors from Kurukshetra, Matsya, Surasena, and Panchala.

- Warriors like Commander Suraja, Śri Śakho Sanehi Jha, Pundamalla Miśra (expert archer), and Rajadeva (Raut) played key roles in battles.

Cultural Flourishing under Shiva Simha Singh

Shiva Simha Singh was a great patron of the arts, supporting the Maithili language and literature. The renowned poet Vidyapati, often called the father of Maithili literature, flourished under his rule. His works brought a cultural revival in Mithila, which had remained stagnant under the non-native Karnats.

Decline and the Rise of Raj Darbhanga

The last ruler of the dynasty was Laxminath Singh Deva, who attempted to assert himself as an independent ruler. However, he was assassinated by Nusrat Shah of Bengal, leading to a period of lawlessness in Mithila for 30 years. During this time, Rajput clans battled for power. Eventually, the Maithil Brahmin dynasty of Raj Darbhanga emerged as the dominant force.

Economic and Social Aspects:

Slavery in the Oiniwar Period

Evidence suggests that slavery was practiced during the Oiniwar rule. Multiple deeds of sale for slaves, dating to the 15th and 16th centuries, were written in Maithili on palm leaves.

- These deeds often included conditions preventing slaves from escaping.

- Some individuals sold themselves into slavery for financial reasons.

- Slavery was mentioned in the reigns of Bhairavasimha and his son Ramabhadra.

Numismatics: Coins of the Oiniwar Rulers

Coins from the Oiniwar dynasty have been discovered, offering insights into their rule.

- Gold coins from Shiva Simha Singh (recovered in 1913) bore the inscription “Sri Sivasya” and were likely used for limited circulation.

- Silver coins from Bhairavasimha were found in Bairmo, Darbhanga district. These were issued around 1489-1490 and bore the inscription:

- “Bhairavasimha, Lord of Tirabhukti and son of Darppanārāyana.”

Sources of Historical Information

The chief sources of Oiniwar history include:

- Vidyapati’s writings, who served seven kings and two queens of the dynasty. His Kīrtilatā, a prose poem, was commissioned by King Kirtisimha.

- Inscriptions such as the Bhagirathpur inscription, discovered in Darbhanga, provide genealogical details of Kansanarayana, the last Oiniwar king.

- Coins and historical records analyzed by numismatists like Dineshchandra Sircar.

The Oiniwar dynasty (1325-1526) was a crucial period in Mithila’s history. Though they ruled as vassals of the Delhi Sultanate, they revived Maithili culture, literature, and governance. The era saw shifts in political power, military struggles, and economic developments. With the assassination of Laxminath Singh Deva, the dynasty fell into decline, eventually paving the way for the rise of Raj Darbhanga, which would dominate Mithila in later centuries.

The Pithipati Dynasty (1120-1290 CE)

Origins and Background:

During the late Pala period, the Pithipatis of Bodh Gaya ruled the Magadha region from the 11th to 13th centuries CE. The term “Pithipati” refers to the Diamond Throne (Vajrasana) under which the Buddha is believed to have attained enlightenment. The Pithipatis, also called the Pithis of Magadha, were initially religious authorities and later transitioned into political rulers.

They were Buddhist kings and patrons of the Mahabodhi Temple, often referring to themselves as Magadhadipati (rulers of Magadha). The historian Dineshchandra Sircar suggests that they originally served as priests before gaining political power, likely as subordinates of the Pala dynasty.

Genealogy and Dynastic Lineage:

The Pithipatis belonged to the Chinda and Chikkora clans, which traced their origins to the Chindaka Nagas of Bastar (modern-day Chhattisgarh). They were originally noblemen and advisors to the Kalachuris of Ratnapura. The first known Pithipati ruler, Vallabharaja, migrated to Bodh Gaya, converted to Buddhism, and took the monastic name Devaraksita.

List of Rulers and Reigns:

- Vallabharaja (Devaraksita) (1120–1160 CE) – Founder of the dynasty, established power in Bodh Gaya.

- Desaraja (1160–1180 CE) – Successor and consolidator of the dynasty.

- Devasthira (1180–1200 CE) – Continued governance and temple patronage.

- Buddhasena (1200–1240 CE) – Strengthened ties with Sri Lankan monks.

- Purnabhadra (1240–1255 CE) – Maintained dynastic rule amid external threats.

- Jayasena (1255–1280 CE) – Last well-documented ruler.

- Sangharaksita, Buddhasena II, and Madhusena (Post-1280 CE) – Lesser-known rulers who governed during the dynasty’s decline.

Rise to Power and Political Relations:

- Vallabharaja’s campaign against the Palas: Initially a noble from Ratanpur, Vallabharaja launched a campaign against Ramapala, establishing Bodh Gaya as his base. He overthrew the ruling Yakspala dynasty and married the daughter of Mahana Pala (uncle of Ramapala) to make peace.

- Relations with the Gahadavalas: Vallabharaja’s daughter, Kumaradevi, married Govindachandra of the Gahadavala dynasty, solidifying an alliance to counter Pala influence.

- Conflict with the Karnats of Mithila: The Karnat prince, Malladeva, briefly ousted a Pithipati ruler (possibly Devaraksita) but was later defeated by the Gahadavala king (likely Jayachandra), who restored Pithipati rule in Bodh Gaya.

Cultural Contributions and Religious Patronage:

The Pithipatis were significant patrons of Buddhism, particularly in the Magadha region.

- Buddhasena’s land grants: Inscriptions mention donations to Sinhalese monks (Singhalasangha) and land grants to Mangalavamsin, a monk from Sri Lanka.

- Monastic and temple support:

- Repaired the Odantapuri monastery.

- Donated land to the Telhara monastery.

- Sponsored monks at Nalanda.

- Kumaradevi’s inscription at Sarnath: Indicates her Buddhist faith and confirms her father, Devaraksita, as a Pithipati ruler.

Decline and External Threats:

The Pithipatis faced increasing external pressures during the 13th century:

- Turkic invasions: During Buddhasena’s reign (1200–1240 CE), the region was raided by Turkic forces. Tibetan traveler Dharmasvamin (1234–35 CE) reported that Buddhasena had retreated into the forests, leaving the Mahabodhi Temple fortified with only four monks present.

- Post-Pala transition: After the decline of the Pala dynasty, the Pithipatis likely switched allegiances between competing regional powers.

- Survival after Bakhtiyar Khalji’s invasion: Some evidence suggests that the Pithipatis remained influential even after the invasion, as inscriptions indicate continued support for Buddhist monasteries.

Territorial Extent:

At their peak, the Pithipatis controlled Gaya, Magadha, and parts of Munger district. An inscription found in Arma, Munger suggests their influence extended beyond Bodh Gaya.

The Pithipati dynasty (1120–1290 CE) played a crucial role in preserving and promoting Buddhism in Magadha. Despite operating under the shadow of larger powers such as the Palas, Karnats, and Gahadavalas, they managed to maintain their autonomy. However, Turkic invasions and shifting political landscapes eventually led to their decline by the late 13th century.

The Chero Dynasty

The Chero dynasty, also known as the Chyavana dynasty, was a ruling polity that emerged in the northern regions of the Indian subcontinent, spanning the modern-day states of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Jharkhand. Their rule began after the decline of the Pala Empire and lasted from the 12th century to the 19th century. While initially independent, they later became tributaries to the Mughal Empire and were eventually reduced to the status of local chieftains and zamindars.

Territorial Extent and Political Influence:

At the peak of their power, the Chero kingdom stretched from the Upper Gangetic plain in the west to the Lower Ganga plain in the east, and from the Madhesh region in the north to the Kaimur Range and the Chota Nagpur Plateau in the south. Their territory extended from Prayagraj in the west to Banka in the east and from Champaran in the north to the Chota Nagpur Plateau in the south. They established several principalities in Shahabad, Saran, Champaran, Muzaffarpur, and Palamu.

Major Capitals and Rulers

- Bihea – Capital of Raja Ghughulia.

- Tirawan (Bhojpur region) – Second capital, ruled by Raja Sitaram Rai.

- Chainpur – Ruled by Raja Salabahim.

- Sasaram (Deo Markande) – Ruled by Raja Phulchand.

Conflict with Sher Shah Suri:

According to Ahmad Yadgar, Sher Shah Suri sought to obtain a white elephant from the Cheros. Upon their refusal, Sher Shah dispatched Khawas Khan with 4,000 cavalry to subdue them. The Chero chief was besieged, forced to surrender the elephant, and suffered defeat. According to Abbas Sarwani, the author of Tarikh-i-Sher Shahi, the Chero ruler became a significant power in Shahabad, leading Sher Shah to send Khawas Khan on another expedition against him. However, the campaign was suspended due to the Battle of Chausa.

Chero Resistance Against Mughal Rule:

1590: Attack by Raja Man Singh

In 1590, Raja Man Singh, after subduing the chiefs of Kharagpur and Gidhour, attacked Anant Rai of Palamu. Despite their resistance, the Cheros were ultimately defeated, with many killed and taken as prisoners. Palamu was brought under Mughal administration. However, after Akbar’s death, Anant Rai expelled the Mughal forces and declared independence in 1607.

17th Century: Pratap Rai and Mughal Campaigns

During the reign of Shah Jahan, the Cheros of Palamu, led by Pratap Rai, began to raid Mughal-controlled districts. In response, Mughal governor Shaista Khan led an expedition against them. Due to the dense forests and hilly terrain, the Mughals struggled to capture Palamu Fort, but after six months, Pratap Rai surrendered.

Conflicts with the Ujjainiya Rajputs:

The Cheros lost their territory in western Bihar to the Ujjainiya Rajputs in the 14th century under Hunkar Sahi’s leadership.

In 1607, Chero chieftains launched counterattacks to reclaim their lands. Kumkum Chand Jharap, a descendant of Sitaram Rai, successfully drove out the Ujjainiyas from the Bhojpur region. However, Ujjainiya ruler Narayan Mal sought imperial Mughal assistance from Jahangir and regrouped his forces.

The Battle of Tirawan (1611)

In 1611, a decisive battle took place at Tirawan:

- The Cheros fortified their position with reinforcements from the Raja of Khaddar, Anandichak, and Balaunja (Japla).

- The battle lasted 21 days, with the Cheros initially repelling the Ujjainiyas.

- Ujjainiya reinforcements, led by Mughal general Thakur Rai Kalyan Singh, turned the tide.

- The Cheros fought valiantly but were ultimately defeated.

- Many Chero leaders, including Sharan Jharap, Raja of Lohardaga, and Raja Madha Mundra, were killed.

- Deogaon and Kothi forts were destroyed, marking the downfall of Chero power in Bhojpur.

Narayan Mal, now undisputed leader of the Ujjainiyas, eliminated Chero control in the region. However, he was later assassinated in a family feud.

The Chero dynasty played a crucial role in the history of Bihar and Jharkhand, resisting Turkic, Rajput, and Mughal forces for centuries. Despite their decline in the 17th century, they left a significant mark on regional history, with their legacy enduring through inscriptions, local traditions, and historical texts.

Khayaravala Dynasty (11th-13th centuries)

The Khayaravala dynasty was a ruling dynasty that governed the Son river valley region in South Bihar and parts of Jharkhand during the 11th to 13th centuries. Their rule was marked by significant territorial control and contributions to fortifications, particularly the Rohtasgarh Fort.

Origins and Capital:

The Khayaravalas were a tribal kingdom whose capital was located at Khayaragarh, in what is now the Shahabad district of Bihar. They ruled over the Japila (Japla) territory, primarily as feudatories under the Gahadavala dynasty of Varanasi.

Notable Kings:

- Pratapdhavala: A significant ruler of the dynasty who undertook various administrative and military initiatives.

- Shri Pratapa: Another prominent king, known for his patronage and contributions to infrastructure.

Feudal Ties and Influence:

Evidence of the Khayaravala dynasty’s feudal ties with the Gahadavala dynasty comes from inscriptions that indicate land grants made to the Khayaravalas. Their governance reflected a mix of independence and allegiance to the larger ruling powers of the time.

Contribution to Architecture:

One of the most notable contributions of the Khayaravala dynasty was their involvement in the construction and fortification of Rohtasgarh Fort. This fort played a crucial role in regional defense and later historical events.

Decline:

The dynasty eventually faded from prominence by the 13th century, likely due to the changing political landscape, external invasions, and the rise of other regional powers in Bihar and Jharkhand.

Jaunpur Sultanate (1394–1493) and Its Conflict with the Ujjainiyas

Emergence of the Jaunpur Sultanate:

The Jaunpur Sultanate was established in 1394 following the weakening of the Delhi Sultanate. It emerged as a powerful regional entity in North India and extended its influence over Western Bihar. Several coin hoards and inscriptions from the Jaunpur period have been discovered in Bihar, attesting to its control over the region.

Conflict with the Ujjainiyas of Bhojpur:

During the reign of Malik Sarwar, the first ruler of the Jaunpur Sultanate, the kingdom became embroiled in a 100-year war with the Ujjainiya Rajputs of Bhojpur in present-day Bihar.

- Early Success of the Ujjainiyas: The Ujjainiya chieftain, Raja Harraj, initially launched a successful resistance against Malik Sarwar’s forces, inflicting significant defeats on the Jaunpur Sultanate.

- Jaunpur Sultanate’s Counterattack: Despite their initial setbacks, the Jaunpur rulers eventually reorganized their military and launched successive campaigns against the Ujjainiyas.

- Shift to Guerrilla Warfare: Unable to match the numerically superior forces of Jaunpur in open battles, the Ujjainiyas retreated into the forests and adopted guerrilla tactics to continue resisting the Sultanate’s expansion.

Legacy of the Conflict:

This prolonged conflict between Jaunpur and the Ujjainiyas shaped the political landscape of Bihar during the 15th century. While the Jaunpur Sultanate managed to maintain control over parts of Bihar, the fierce resistance by the Ujjainiyas ensured that Bhojpur remained a contested region. This period laid the groundwork for further regional power struggles in Bihar, particularly in the aftermath of the decline of the Jaunpur Sultanate.

Early modern period (1526–1757)

The Sur Empire (1538/1540 – 1556): Bihar’s Golden Era Under Sher Shah Suri

Rise of Sher Shah Suri and the Establishment of the Sur Empire:

The Sur Empire was an Afghan-ruled empire that dominated northern India for nearly 16 to 18 years. It was founded by Sher Shah Suri, who hailed from Sasaram, Bihar, and became one of the most influential rulers of medieval India. In 1538/1540, he overthrew the Mughal Emperor Humayun, establishing his rule over a vast territory stretching from Balochistan in the west to Rakhine (modern-day Myanmar) in the east. Bihar, especially Sasaram and Patna, played a crucial role as the seat of Sur power in India.

Sher Shah’s Administrative and Economic Reforms:

Sher Shah Suri is remembered for his landmark administrative, economic, and infrastructural reforms, many of which remain influential today:

- Grand Trunk Road: He built the longest road of the Indian subcontinent, the Grand Trunk Road, stretching from Calcutta (Bengal) to Peshawar (now in Pakistan), significantly enhancing trade and connectivity.

- Economic Reforms: He introduced the Rupee, which laid the foundation for modern Indian currency, and custom duties that streamlined trade regulations.

- Revival of Patna: Sher Shah revived and developed Patna, making it a key administrative and commercial center, where he built his headquarters.

Hemu: The Hindu General and Brief ‘Hindu Raj’:

- Hemu, a self-made Hindu general and administrator, rose from humble beginnings as the son of a food vendor in Rewari to become the Chief of Army and Prime Minister under Adil Shah Suri, a later Sur ruler.

- He defeated Akbar’s Mughal forces twice, at Agra and Delhi (1556), and briefly established a Hindu Raj in North India, ruling from Purana Qila in Delhi.

- However, his reign was short-lived as he was killed in the Second Battle of Panipat the same year, marking the end of Sur rule and the restoration of Mughal power under Akbar.

Legacy of the Sur Empire:

Despite its relatively short rule, the Sur Empire left a lasting impact on Indian administration, economy, and infrastructure. Sher Shah’s governance model was later adopted by Akbar and formed the basis of the Mughal administrative system. Bihar, particularly Sasaram, remains a significant historical site associated with Sher Shah Suri’s legacy.

The History of Zamindari in Bihar: From Mughal Rule to Post-Independence Reforms

The zamindari system played a crucial role in shaping the socio-economic and political landscape of Bihar during the Islamic and British periods. This system, characterized by powerful landowners maintaining control over vast estates, continued until the abolition of zamindari post-independence. The history of Bihar’s zamindars reflects a tale of power struggles, feudal dominance, and eventual socio-political transformation.

Zamindari Under Islamic Rule:

During the Islamic rule, much of Bihar remained under the sway of local zamindars or chieftains who maintained their own armies and exercised substantial autonomy. These chieftains retained power until the arrival of the British East India Company.

In 1576, after the Battle of Tukaroi, Mughal Emperor Akbar annexed the Bengal Sultanate, integrating Bihar into his empire. Bihar was designated as one of the twelve original subahs, with its seat at Patna (Azimabad). The region remained under Mughal control until the Battle of Plassey in 1757.

Prince Azim-us-Shan, grandson of Aurangzeb, was appointed as Governor of Bihar in 1703. He renamed Patna as Azimabad in 1704. The Bihar Subah functioned as a crucial link between Hindustan and Bengal and was divided into seven sarkars:

- Bihar

- Monghyr

- Champaran

- Rohtas

- Hajipur

- Saran

- Tirhut